![]() Charles Townsend (1900-1997) moved from London, England to Vancouver in the early 1920's where he met Neal Carter while studying Agriculture at UBC. Townsend was a very active member of the British Columbia Mountaineering Club during his few short years in Vancouver from 1922 to 1925.

Charles Townsend (1900-1997) moved from London, England to Vancouver in the early 1920's where he met Neal Carter while studying Agriculture at UBC. Townsend was a very active member of the British Columbia Mountaineering Club during his few short years in Vancouver from 1922 to 1925.

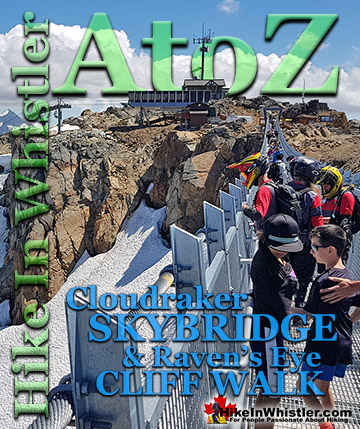

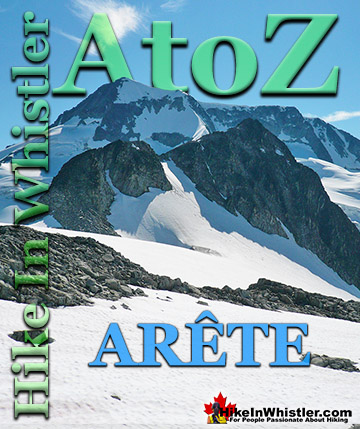

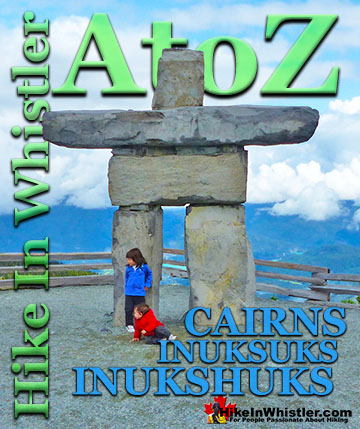

Whistler & Garibaldi Hiking

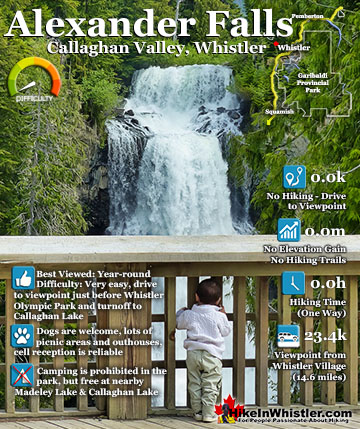

![]() Alexander Falls

Alexander Falls ![]() Ancient Cedars

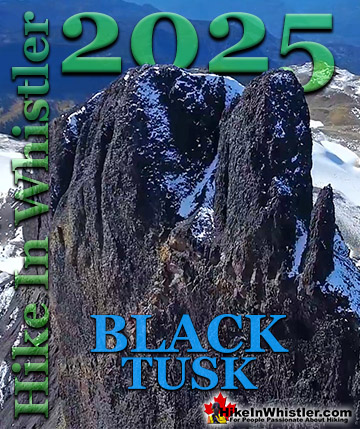

Ancient Cedars ![]() Black Tusk

Black Tusk ![]() Blackcomb Mountain

Blackcomb Mountain ![]() Brandywine Falls

Brandywine Falls ![]() Brandywine Meadows

Brandywine Meadows ![]() Brew Lake

Brew Lake ![]() Callaghan Lake

Callaghan Lake ![]() Cheakamus Lake

Cheakamus Lake ![]() Cheakamus River

Cheakamus River ![]() Cirque Lake

Cirque Lake ![]() Flank Trail

Flank Trail ![]() Garibaldi Lake

Garibaldi Lake ![]() Garibaldi Park

Garibaldi Park ![]() Helm Creek

Helm Creek ![]() Jane Lakes

Jane Lakes ![]() Joffre Lakes

Joffre Lakes ![]() Keyhole Hot Springs

Keyhole Hot Springs ![]() Logger’s Lake

Logger’s Lake ![]() Madeley Lake

Madeley Lake ![]() Meager Hot Springs

Meager Hot Springs ![]() Nairn Falls

Nairn Falls ![]() Newt Lake

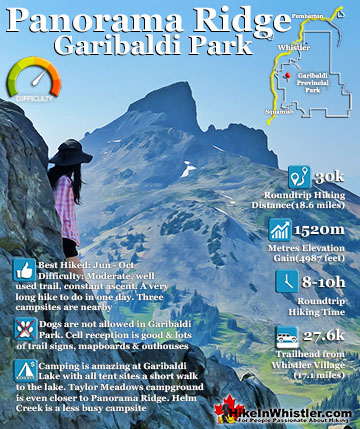

Newt Lake ![]() Panorama Ridge

Panorama Ridge ![]() Parkhurst Ghost Town

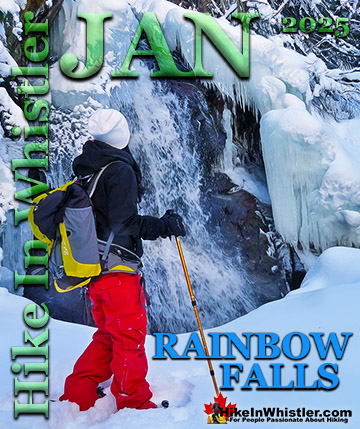

Parkhurst Ghost Town ![]() Rainbow Falls

Rainbow Falls ![]() Rainbow Lake

Rainbow Lake ![]() Ring Lake

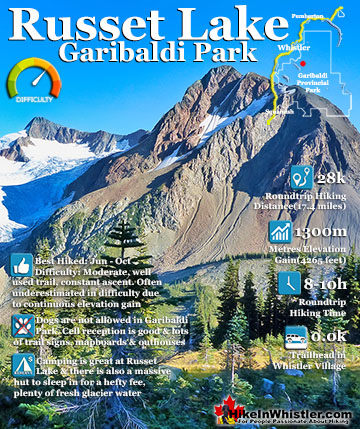

Ring Lake ![]() Russet Lake

Russet Lake ![]() Sea to Sky Trail

Sea to Sky Trail ![]() Skookumchuck Hot Springs

Skookumchuck Hot Springs ![]() Sloquet Hot Springs

Sloquet Hot Springs ![]() Sproatt East

Sproatt East ![]() Sproatt West

Sproatt West ![]() Taylor Meadows

Taylor Meadows ![]() Train Wreck

Train Wreck ![]() Wedgemount Lake

Wedgemount Lake ![]() Whistler Mountain

Whistler Mountain

![]() January

January ![]() February

February ![]() March

March ![]() April

April ![]() May

May ![]() June

June ![]() July

July ![]() August

August ![]() September

September ![]() October

October ![]() November

November ![]() December

December

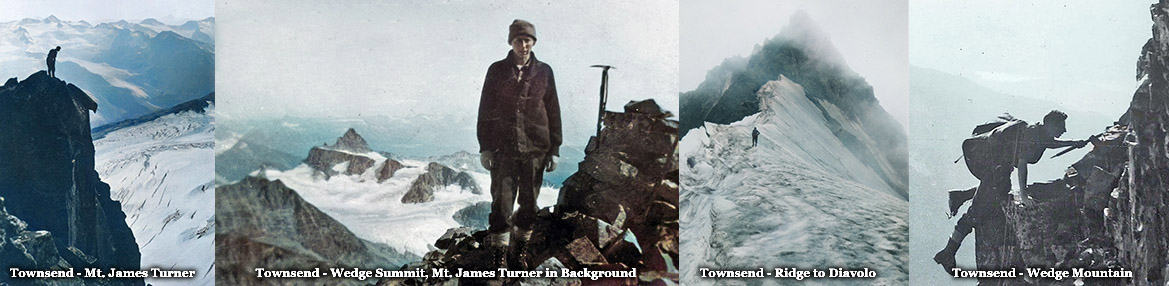

In 1922 Townsend and Carter teamed up and made first ascents and also named two prominent peaks of Garibaldi Park, The Bookworms and Deception Peak. They worked together in the summer of 1923 as surveyors for the hydroelectric project that would eventually result in the hydro dam on Daisy Lake along the Sea to Sky Highway. At the end of the summer when the survey work was finished, they went on a spectacular two-week expedition into the mountains around the valley now home to Whistler. Their first goal was Wedge Mountain which they recorded the first ascent. From the summit of Wedge, they spotted a striking mountain in the distance and in the next two days they made their way across unknown glaciers to climb and also name the peak they called Mount James Turner. A few days later they explored up the Fitzsimmons Valley which ascends between Blackcomb and Whistler mountains, to the peaks of Overlord Mountain. They made first ascents and named several peaks they encountered. They also spent a day hiking to the summit of Whistler Mountain via the route we now know as the Musical Bumps. Along the way Neal Carter took incredible photos which he gave to Myrtle Philip at Rainbow Lodge and now reside at the Whistler Museum.

Wedge & Whistler Expedition in 1923

These are some of Neal Carter's photos now at Whistler Museum. The have been colorized. The picture on the far left is of Charles Townsend standing on a cliff near the summit of Mount James Turner on September 12th 1923. The second picture shows Townsend standing next to the cairn they built on the summit of Wedge Mountain, two days previously, with Mount James Turner visible in the distance. The third picture is Townsend on the ridge to Diavolo Peak on September 18th, 1923. The fourth picture is of Townsend climbing Wedge Mountain on September 10th, 1923.

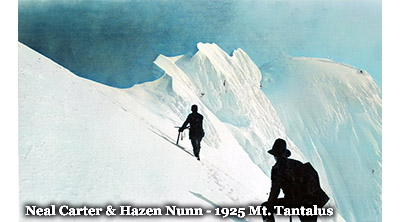

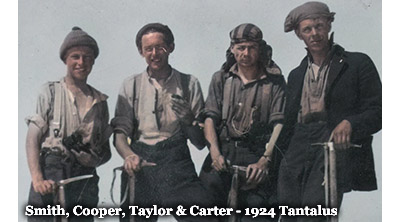

Tantalus Expedition in 1925

In 1925 Charles Townsend, Neal Carter and Hazen Nunn went on an expedition into the Tantalus Range, hoping to reach the summit of Mount Tantalus. They were unsuccessful in reaching the summit, however they wrote about the journey and took some incredible photos Carter compiled into photo albums which made their way to the MONOVA Museum in Vancouver. These are some of Carter's photos which have been colorized to bring them more to life.

Charles Townsend UBC, McGill & Berkeley

Charles Townsend graduated UBC with a B.S.A in 1925 and attended McGill University in Montreal in 1926. The UBC Grad Book in 1925 has a photo and a funny write up which recalls his love of the mountains:

Charles Townsend graduated UBC with a B.S.A in 1925 and attended McGill University in Montreal in 1926. The UBC Grad Book in 1925 has a photo and a funny write up which recalls his love of the mountains:

CHARLES THOREAU TOWNSEND. "I hate the town, I cannot live within its gates." Charley is the great open-spacer of the Aggie Undergrad, and any Sunday you'll find him rushing from peak to peak on the mountains of the North Shore. If he looks over the top and sees some country that appeals to him, he just packs up and heads for it, that's all. He's a determined tennis fiend and is the only man in the University who can smoke a pipe in the Bacteriology lab, and get away with it.

Townsend likely studied at McGill until 1929 as Neal Carter did to get his PhD, though details of his life after leaving Vancouver in 1925 are scarce. He moved to Berkeley, California at some point after McGill as he authored articles in 1954, 1959 and 1966 which appeared in agricultural journals that list him as Charles T. Townsend, Berkeley, California.

First Ascents by Charles Townsend

- 1922 The Bookworms first ascent and named with Neal Carter.

- 1922 Deception Peak first ascent and named with Neal Carter.

- 1923 Wedge Mountain first ascent with Neal Carter.

- 1923 Mount James Turner first ascent and named with Neal Carter.

- 1923 Whirlwind Peak first ascent and named with Neal Carter.

- 1923 Diavolo Peak first ascent and named with Neal Carter.

1923: Wedge & Whistler Expedition

Charles Townsend & Neal Carter

Townsend climbed and explored several mountains around Whistler back in 1923, when much of the area remained unexplored. Along with his friend Neal Carter, they embarked on a mountaineering expedition that was recorded in detail and expertly photographed. Wedge Mountain, the strikingly wedge-shaped mountain next to Blackcomb Mountain was first climbed by them, and the following days they pressed on through unknown glaciers to summit and name Mount James Turner. Mount James Turner is the third highest mountain in Garibaldi Provincial Park at 2703 metres(8868 feet). It is only surpassed by Wedge Mountain at 2892 metres(9488 feet) and Wedge's neighbour Mount Weart 2835 metres(9301 feet). Mount James Turner is quite a remote mountain in Garibaldi Park and takes about 8 hours to reach it from Wedge Mountain. Remarkably, this expedition was documented by both Townsend and Carter, as well as photographed by Carter. Despite the largely uncharted terrain which involved bushwhacking, large creek crossings, treacherous, unknown mountains and numerous glacier crossings, the story reads as a relatively mild walk in the woods. Certainly they were extremely tough, skilled and fearless mountaineers that had a love of exploring mountains that is inspiring to read. Hearing the word for word account gives you the beautiful sense that you are with them on their journey through these mountains as they were first climbed. Charles Townsend wrote two articles about their two week expedition in the BC Mountaineer newsletter. The first in October 1923 with the title, 'Trip to Wedge Mountain and Mt. Turner'. The second, 'Fitzsimmons Creek Mountains', was printed in November 1923. His articles are shown below in bold. Neal Carter's photographs have been added to the article as well as dates and headings to clarify where they were on each day. Neal Carter's black and white photos have been partially colorized to enhance their appearance.

Charles Townsend's 1923 BC Mountaineer Articles

BCMC Newsletter October 1923

TRIP TO WEDGE MOUNTAIN AND MT. TURNER

By Chas. T. Townsend

Mr. Neal Carter and I had been planning all the summer to make the first ascent of Wedge Mt. as soon as we could get away in the fall. Accordingly on Saturday evening, September 8th, we landed with our belongings at Alta Lake. Having nearly a fortnight before us, we decided to make Rainbow Lodge our headquarters, and to make two trips, one up Wedge Mountain, and the other to Avalanche Pass, the proposed 1923 camp site.

September 9, 1923: Alta Lake to Camp #1 on Parkhurst Mountain

We left half our grub at the Lodge, and with the other half and the rest of our belongings, started out from Alta Lake on Sunday morning bound for Wedge Mountain. We followed the railway for 4 miles to Mile 42, as from Rainbow Lodge we could see that the main ridge from Wedge Mountain hit the railway at about this point. From the railway we travelled east following logging roads for about a mile, and after that picking our way through the trees (there was very little bush), for another half-mile until we reached Wedgemount Creek, where we had lunch. Our journey so far had taken us 3 hours. Wedgemount Creek was larger than we had expected, and we were lucky in finding a log on which to cross quite a short distance above where we struck the creek.

Neal Carter Wedge Creek Log Crossing 9 Sept 1923

On the east side, the hill rises very sharply from the water for about 800 feet, and as the bush was thick, we were very glad of a rest when we reached the top. From there on, the ridge is a succession of bluffs, thickly wooded.

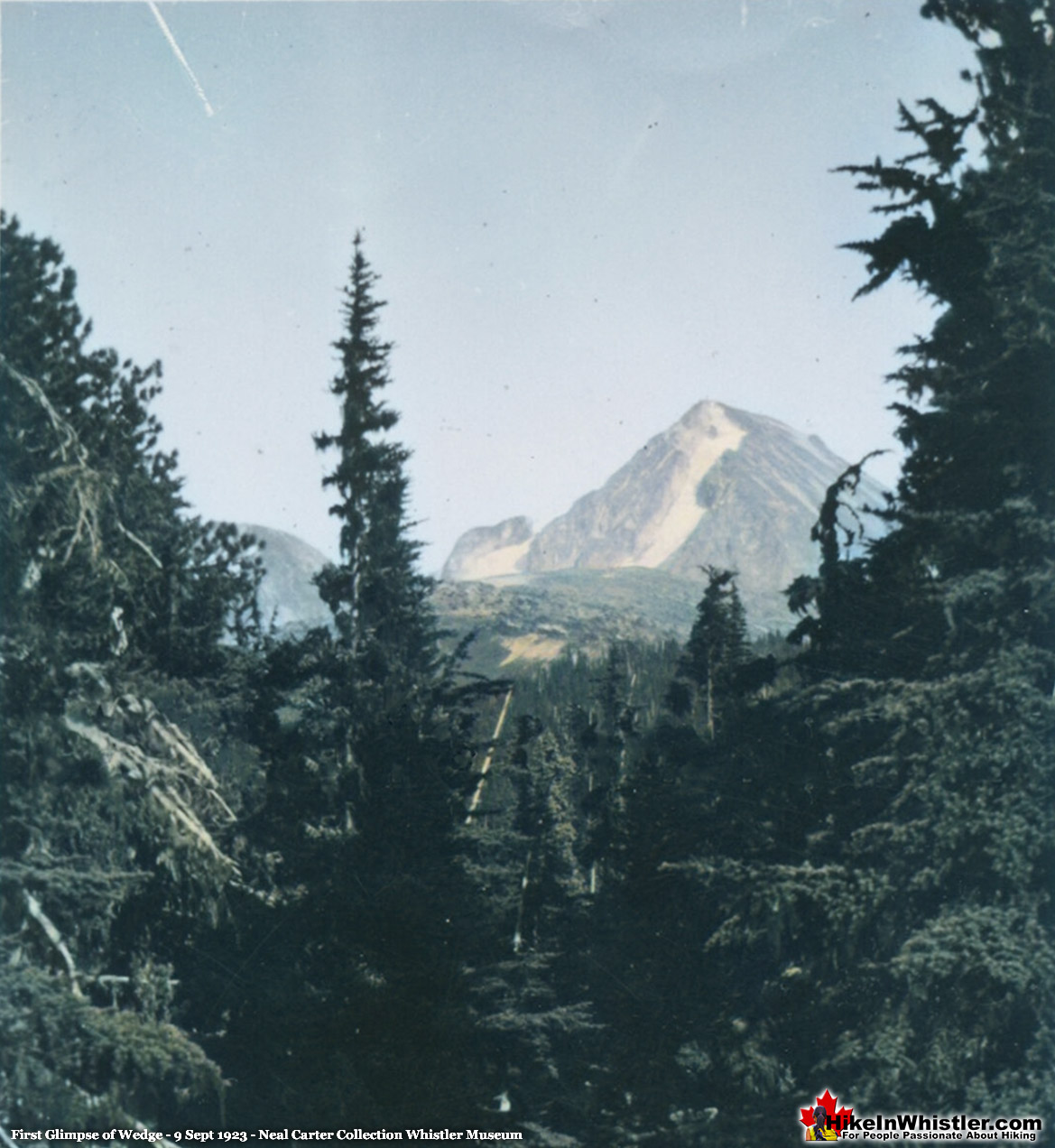

First Glimpse of Wedge Mountain 9 Sept 1923

At about 5,000 feet elevation the trees thinned out, giving place to meadows, which must have been beautiful when the flowers were in bloom. We were nearly “all in” when we found water at about 6 pm, and we made camp as quickly as possible. We were now in an ideal place for an attempt on Wedge Mountain, being at an elevation of 6,000 feet, and at the extreme limit of timber line.

September 10, 1923: Wedge Mountain

Early the next morning we started up the ridge. At the end of it we found quite a gap in between us and the base of the mountain, and I should suggest to any others who might make the climb, that it would be more advisable to keep on the south side of the ridge at an elevation of about 6,000 feet, instead of climbing to the top of it. This would bring them to the foot of the gap and at the base of the easiest face of Wedge Mountain.

Wedge Mountain from Ridge Above Camp 10 Sept 1923

As it was, we had to descend into the gap, cross a number of ridges composed of masses of loose rocks, probably moraines at one time, and then cross a small glacier, before we got on to the climbable slopes of the mountain. The glacier we named “Eclipse Glacier.”

Charles Townsend Eclipse Glacier 10 Sept 1923

From there to the peak, about 2000 feet, we were travelling over talus slopes, the rocks being on an average cubes about 2 feet in thickness. We reached the summit at 115, after having had a good view of a partial eclipse of the sun a short time before.

Charles Townsend West Face Wedge Mountain 10 Sept 1923

Charles Townsend Wedge Summit Looking East 10 Sept 1923

The summit of the Mountain is a long ridge ending in quite a sharp peak at the eastern end. It is very precipitous on three sides, but is readily accessible on the south side, up which we had come.

Charles Townsend Wedge Mountain First Ascent 10 Sept 1923

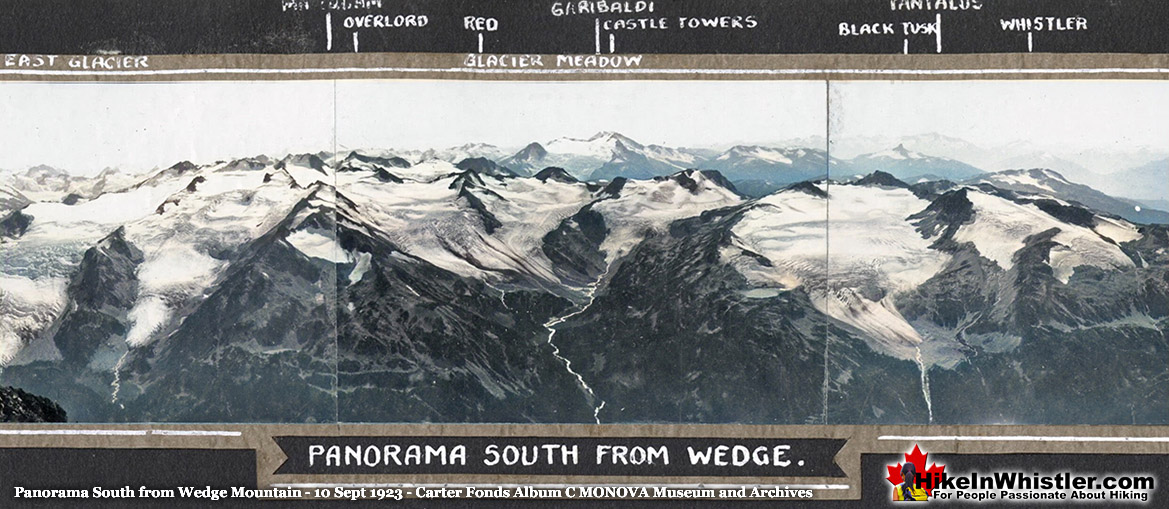

Owing to the clearness of the atmosphere, we had a magnificent view, and were able to secure some fine photographs. Immediately to the south of us was the Spearhead Range, which has been practically unexplored. It contains seven fine glaciers on the north side, and, as we afterwards discovered, one on the south side. What particularly attracted us was a valley immediately south of the peak of Wedge Mountain. This valley pointed north and south, and contains beautiful meadows. At the head of it, on three sides, there are three large glaciers, one of which has a splendid ice-fall. The meadows are probably at an elevation of about 5,500 feet, and they lie in the centre of the Spearhead Range, so that a party intending to climb in that district would do well to investigate the possibilities of a camp there. We named the place “Glacier Meadows.” It would also seem to be possible to climb peaks in the Fitzsimmons district from there, as there is quite a low pass over to the Fitzsimmons Valley. Mt. Overlord, and a number of other peaks at the head of the Fitzsimmons glacier, possibly could be climbed in a day's trip.

Panorama South from Wedge Mountain 10 Sept 1923

On the north side of Wedge Mountain are several large glaciers, one of which we called “Wedge Glacier,” and another the “Crescent Glacier.” To the east of us lay a peak which we resolved should be the object of our next climb. It lay across a valley from Wedge Mountain, and promised to be an enjoyable three-day trip from camp.

First View of Mt James Turner from Summit of Wedge Mountain 10 Sept 1923

Whistler Museum's Virtual First Ascent of Wedge Mountain

In 2012, Jeff Slack, working at the Whistler Museum created three wonderful videos of the Carter/Townsend expedition. He used the written account of Charles Townsend and the photos taken by Neal Carter. He narrated the videos along with images from Google Earth, recreating the journey in beautiful detail. This is the first of the three videos, The 1st Ascent of Wedge Mountain - A Virtual Tour, which covers the journey from Rainbow Lodge to the summit of Wedge Mountain.

September 11, 1923: Hike Around Wedge to Camp #2

The next day, taking with us just enough food for three days and our bedding, and leaving our tent behind, we hiked round the southern slopes of Wedge Mountain, keeping just above timber line to avoid the bush.

Neal Carter About to Leave Camp 11 Sept 1923

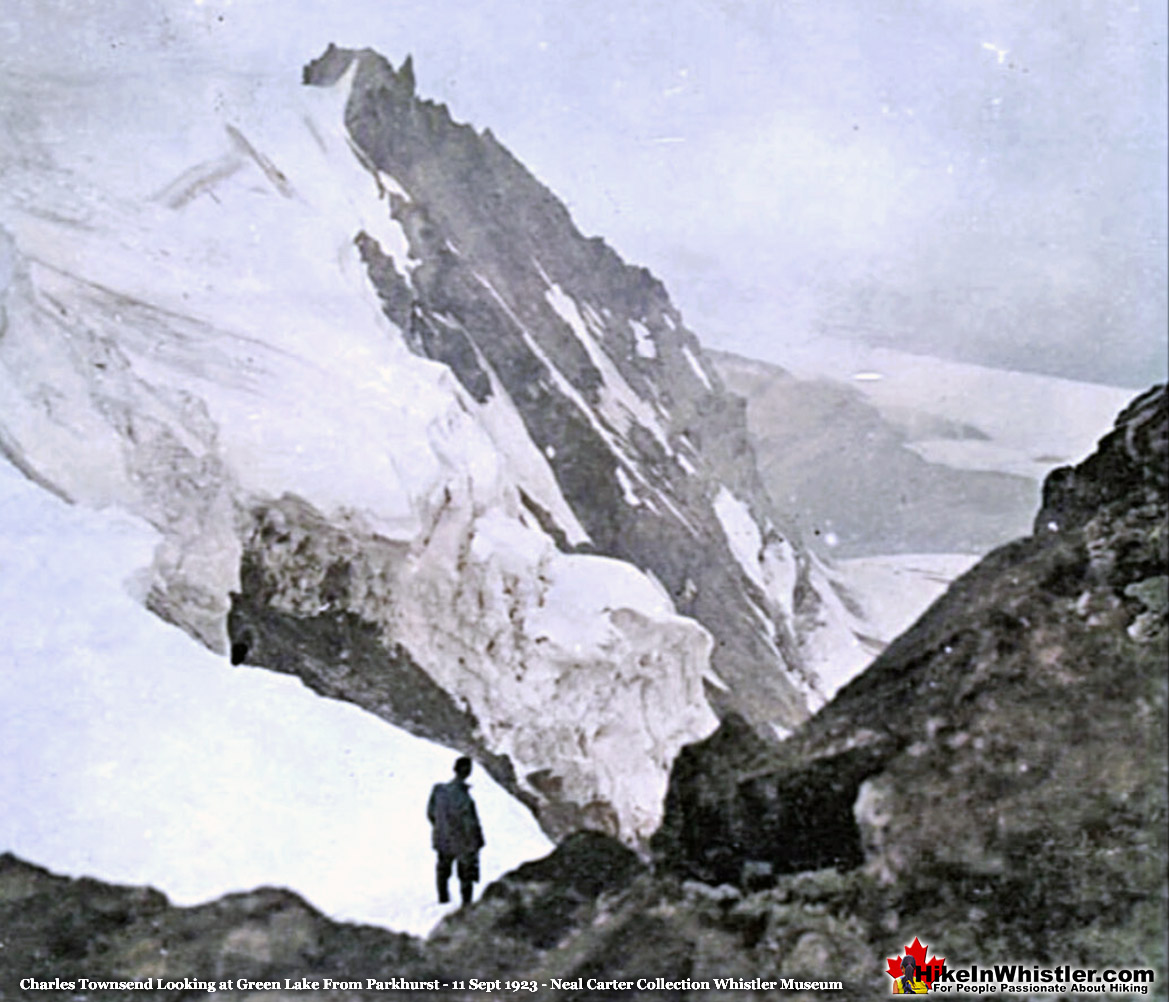

Charles Townsend Looking at Green Lake from Above Parkhurst Camp 11 Sept 1923

To obtain water we had to drop down about 800 feet into the valley east of Wedge Mountain, which we had seen the day before, where we found a delightful camping spot. The journey from camp to camp took us about 5 hours. We lulled ourselves to sleep under the stars that night with soothing strains from the camp orchestra.

September 12, 1923: Mount James Turner

The first part of our climb the next day took us over four high ridges, very much similar in composition to Wedge Mountain. This brought us to an elevation of about 7.000 feet, where we came out on to a glacier which we called the “Quarry Glacier” From there we had a good view of the peak of Mt. Turner, as Neal had named it, in memory of the Rev. Jas. Turner. Once across the Quarry Glacier, we had to cross the Turner Glacier, much larger than the former, and flowing east, while the other flowed west towards Wedge Mountain.

Neal Carter on Turner Glacier (now Chaos Glacier) 12 Sept 1923

We were now at the foot of the cliffs at the base of the peak. These cliffs run east and west from the base of the peak; on the west side they form a striking ridge of jagged rock surmounted by fantastic pinnacles. Owing to this peculiarity we called it “Finger-post Ridge” We had some trouble getting up the cliffs to the east of the peak owing to the extreme looseness of the rocks, but once on top, we were ready for the final climb. The peak is a mass of jagged rock, most of which is very loose and dangerous, and I doubt whether it could be climbed from any direction other than the east. An hour's rock-climbing took us to the summit, where we arrived at 1:30. The top itself was so small that it was hardly big enough for a cairn. On three sides the cliffs were very precipitous, while even the face up which we had come looked very steep from above.

Charles Townsend James Turner Summit 12 Sept 1923

Once again we had a magnificent view, particularly of Wedge Mountain, which looks very fine from that side. Three glaciers to the north we named respectively, “The Chaos,” “The Needle,” and “The Albert Edward” glaciers.

Charles Townsend Mount James Turner 12 Sept 1923

We reached camp again at about 6 p.m.

September 13, 1923: Camp #2 to Camp #1

Townsend does not write about September 13th which was spent moving from their second camp to their first camp on Parkhurst Mountain.

September 14, 1923: Camp #1 to Alta Lake

The next day we packed back to our first camp, and the day following down to Alta Lake, the latter journey taking us six hours. Our aneroid was found to be untrustworthy, so we had to estimate our elevations from well-known peaks in the Garibaldi district. Thus we made Wedge Mountain to be 8,400 feet high, or higher than Castle Towers, and Mt. Turner to be 8,000 feet, or 400 feet lower than Wedge Mountain. At Rainbow Lodge we had an excellent supper, which partially made up for a week of dried goods, and afterwards collected the other half of our grub preparatory to making an early start the next day up Fitzsimmons Creek.

Whistler Museum's Virtual First Ascent of Mount James Turner

This is the second of three videos created by Jeff Slack for the Whistler Museum. This one titled, The 1st Ascent of Mount James Turner - Virtual Tour, shows the journey Carter and Townsend went on to reach Mount James Turner. Using Google Earth, Slack follows the route they took, narrates the journey with Townsend's written account, and illustrates it with Neal Carter's beautiful photos.

BCMC Newsletter November 1923

FITZSIMMONS CREEK MOUNTAINS

By Chas. T. Townsend

September 15, 1923: Alta Lake to Fitzsimmons Cabin

We left Rainbow Lodge at 11 a.m. and found the trail up Fitzsimmons Creek was excellent to travel on, and, but for some exciting moments with wasps’ nests, we had an enjoyable day’s journey to the cabin on the meadows below Avalanche Pass. The two miners we found to be not at home, so we made ourselves comfortable in their absence.

Charles Townsend Fitzsimmons Trail 15 Sept 1923

September 16, 1923: The Fissile, Refuse Pinnacle and Overlord

The next day we spent in climbing Mt. Overlord, which had been climbed for the first time by Mr. and Mrs., Munday a few months earlier. They had much more snow for their climb, and were able to go up the Fitzsimmons Glacier from the base of Red Mountain. Owing to the opened up condition of the ice, however, we thought it better to keep to the rocks as much as possible. To avoid the glacier we climbed the east peak of Red Mountain, which connects with Mt. Overlord by a narrow ridge, composed of a series of sharp pinnacles. The rocks were so rotten on this ridge that we called the largest pinnacle “Refuse Pinnacle,” on account of the trouble it gave us in circumnavigating it. Once round this, we got on to the neve of a small glacier, and a short walk took us to the summit of Mt. Overlord.

Neal Carter on Pinnacles Leading to Overlord 16 Sept 1923

Once again we were blessed with a very clear day, and we secured an excellent panorama of the Garibaldi district and the Pitt River mountains, The large Cheakamus Glacier with its huge ice-fall showed up particularly well, and in the distance we could see Mt. Cathedral, of the local mountains, and Mt. Baker in the far distance. Some of the peaks to the east of Mt. Overlord looked as though they might give us some good climbs, one in particular, not far from where we were, looking very inviting.

Peaks from Overlord Looking Northeast 16 Sept 1923

We had no more time that day though, so we went back to the cabin. On our way back we found it easier to go over the top of Refuse Pinnacle, and to drop down to the glacier at the foot of it. We crossed the neve of this to Red Mountain, where we picked up our tracks of the morning.

Charles Townsend on Refuse Pinnacle 16 Sept 1923

Our sleep that night, and every night we spent at the cabin, was seriously disturbed by a couple of large pack rats and a number of mice, which kept up an incessant clatter among the pots and pans, and knocked over everything moveable. The last night we were there it turned much colder, and the pack rats carried a large portion of our firewood from behind the stove to the floor under our bunk, where they were evidently trying to make a nest.

September 17, 1923: Whistler Mountain

On Monday, September 17th, we made a half-day trip to Mt. Whistler. The top is a series of mounds, and it takes some time to find out which is the highest. From the highest point we had a fine view of Rainbow Valley, and the Garibaldi district tempted us to photograph it again, Mt. Whistler is said to be 7,200 feet in height, but it did not seem to us to be any higher than Helmet Peak, 6,800 feet.

Charles Townsend Whistler Mountain 17 Sept 1923

September 18, 1923: Fitzsimmons Cabin to Mount Diavolo

The next day we set out to climb the peak we had seen from the top of Mt. Overlord. We followed our old tracks over Fitzsimmons Glacier and Refuse Pinnacle until we came to the glacier just below the peak of Mt. Overlord. We crossed this in an easterly direction until we came to some pinnacles on a ridge running east from the peak we had just left. The weather up to now had been growing more and more threatening and cold, and at this point the clouds descended on us like a thick fog, accompanied by a high, cold wind, which, however, did not disperse them. We followed the rocks downward towards our objective, of which we occasionally caught a glimpse, and we soon discovered that the only way we could climb it was to cross a knife-edge ridge of ice about 150 feet long, and then find a way up the rocks. Crossing the ice took us some time, as we had to cut steps, Neal breaking his ice-axe in the process.

Charles Townsend on Ridge to Diavolo Peak 18 Sept 1923

The rocks were loose, as usual, and we had an exciting climb to what we thought was the top. We were mistaken, however, for the top was about fifty feet away and about ten feet higher. The only way to it was along a very sharp knife-edge, which we had some trouble in negotiating. Once on top we hurriedly built a cairn, and retraced our steps as soon as possible, for it was bitterly cold. The peak we named Mt. Diavolo, owing to its character and the weather conditions under which we climbed it. Its height we estimated to be about 7,700 feet.

Charles Townsend Straddling Diavolo Summit 18 Sept 1923

September 19, 1923: Fitzsimmons Cabin Rain Turned to Snow

Townsend didn't write about September 19th as it was spent in the cabin avoiding the bad weather.

Charles Townsend Fitzsimmons Cabin 19 Sept 1923

September 20, 1923: Fitzsimmons Cabin to Alta Lake

The next day (19 Sept) it began to snow, keeping up until we left the day after (20 Sept), by which time there was about two inches of snow on the ground.

Whistler Museum's Virtual First Ascent of Mount Diavolo

This is the third of three videos created by Jeff Slack for the Whistler Museum depicting the amazing journey Carter and Townsend went on when they explored the Fitzsimmons Valley to the peaks of Mount Overlord. This one is titled, The 1st Ascent of Mount Diavolo - A Virtual Tour. Using the words of Charles Townsend and the photos of Neal Carter, the video shows the journey with the use of Google Earth.

Neal Carter's Article in The Vancouver Sun 30 Sept 1923

Neal Carter also wrote about the expedition which appeared in the Vancouver Sun in the September 30th, 1923 edition. His excellent article is titled 'Rugged Peaks are conquered in BC Wilds' can be found here.

1925: Fighting Way to Mt. Tantalus

Neal Carter, Charles Townsend & Hazen Nunn

Tantalus Range as we now know it was barely explored when Neal Carter first set his eyes on it in the spring of 1923. All the colorful names we use today were not yet created. The range was dubbed Tantalus Range in the years previously and the tallest, most prominent peak became Mt. Tantalus. Another prominent peak climbed in 1914 was named Alpha by Basil Darling. Omega, Pelops, Niobe, Serratus, and many more were still unnamed peaks. Carter summarized the brief history of early exploration of the range.

Two of the lower summits of the eastern end of the range were ascended in 1910 by a party led by Mr. G.B. Warren. The first account of a mountaineering trip to this range is found in the 1912 Canadian Alpine Club Journal, in which Mr. B.S. Darling of the B.C. Mountaineering Club, relates his exciting experiences in leading a party on the first ascent of Mt. Tantalus in July, 1911. Mr. Darling revisited the region in July, 1914, making the first ascent of Mt. Alpha (7700 feet), which was again climbed in August, 1916, by Mr. Tom Fyles, present director of the B. C, Mountaineering Club, in company with his brother. The latter party also made the first ascent of the lower of the two peaks of Mt. Tantalus.

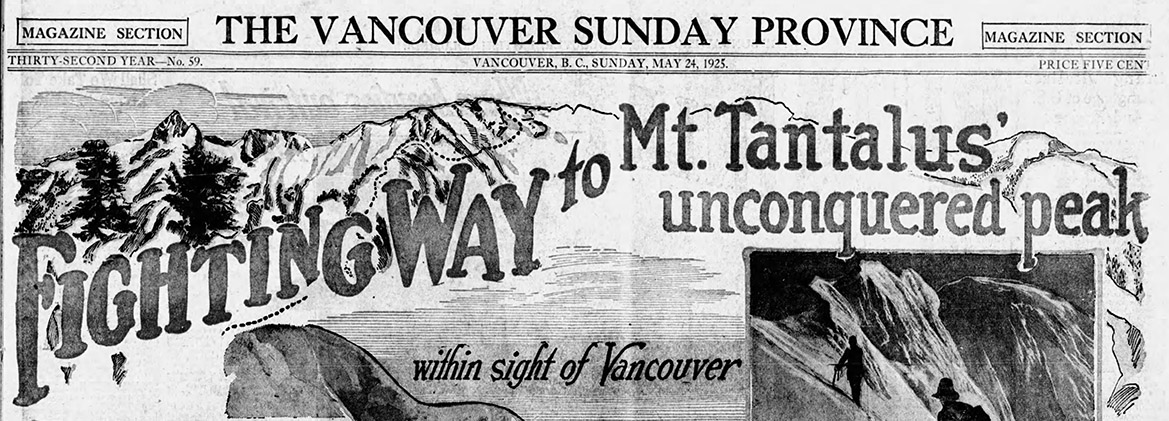

“Fighting Way to Mt. Tantalus’ Unconquered Peak”

On Sunday, May 24th, 1925 the Vancouver Sunday Province had a feature article titled, “Fighting Way to Mt. Tantalus’ Unconquered Peak”. The article was written by Neal Carter just a few days after his third expedition into the Tantalus Range. Three years in a row in springtime he ventured into the challenging and fairly unknown mountain range. This third expedition by Carter, he was joined by Chas Townsend and Hazen Nunn. Townsend was with Carter on his first expedition in 1923 and later that year he and Carter went on their incredible expedition into the unknown mountains around what is now Whistler. Hazen Nunn accompanied Carter on his second expedition into the Tantalus Range in 1924. The highly skilled trio were very motivated and had the ability to reach their goal as Nunn later wrote:

The Tantalus Range runs in a general North-West direction from Howe Sound and can be seen to advantage on the way to Squamish. Although not so extensive as the neighbouring Garibaldi group, it is much more rugged and precipitous. The peaks rise abruptly from the valleys to imposing heights. Mt. Tantalus, the highest peak, overlooking Garibaldi itself. The object of this year’s expedition was to climb Mt. Tantalus which lies in the northern part of the range.

Their 1925 expedition to conquer Mt. Tantalus was unsuccessful, however the expedition was wildly successful in an unexpected way. The photos they took and the articles they wrote bring the historic adventure to life in a beautiful way. It is extraordinary to see a photo of an alpine summit taken a century ago. Photos back then were rare enough, but from a snowy summit after a brutal trek. Extraordinary. The following is the account of the Tantalus expedition in the spring of 1925, mostly taken from Neal Carter's Vancouver Sunday Province article and Hazen Nunn's BC Mountaineer article, both written in 1925.

Day 1: Vancouver to Squamish River Camp

The first day was spent travelling from Vancouver to their first nights camp along Squamish River. From Vancouver to Squamish they travelled by boat ferry. From the boat dock in Squamish they then travelled 30 kilometres by “auto stage” to Chee Kye, a small settlement along Cheakamus River just upstream of the point where it joins Squamish River. They next had to get across Cheakamus River which Carter described, “..by employing “Indian Jim” to take a dugout canoe up the Squamish from Chee Kye, we could cross at the advantageous place used two years previously.” They then made their way to their first camp Hazen Nunn referred to as “Barber's abandoned lumber camp on the south bank.” This camp was in an ideal location leading to what Neal Carter described as “a prominent ridge which led right to the heart of the highest part of the range.”

Day 2: Difficult Hike to Alpine Camp

The next morning, they began the difficult hike up the ridge through dense underbrush and swamp and which Carter described as an “African jungle”. After an hour of difficult bushwhacking, they emerged to more open terrain along the ridge which ascends steeply in a series of bluffs. Carter estimated, “..progress was made at the rate of 1500 feet elevation per hour in places.” Several hours later they reached their second nights camp. Carter wrote, “Towards the end of the day, however, the exertion began to tell, and packs were dropped with much relief at a suitable spot just below the summit. The depth of the snow was estimated at fifteen to twenty feet, and much difficulty was experienced with camp fires, which persisted in eating their way down to a considerable depth, when a fresh one would have to be built. All water was laboriously obtained by melting snow.”

Neal Carter and Hazen Nunn Tantalus Camp - April 1925

Day 3: Attempt on Mt. Tantalus

The third day of the expedition they woke early to climb Mt. Tantalus. Neal Carter detailed the challenging day in detail.

The weather was splendid for an early start the next morning to Mt. Tantalus. The hard snow experienced along the connecting ridge gave way to the soft dry powdery variety when the head of the glacier to the right was reached, however, and it was soon realized that the peak would never be climbed that day. But by plugging along as far as possible, a trail could be made which would enable the ascent to be completed the following day. This was done, therefore, and proved quite dangerous. The party had to rope together, for the glacier is notoriously steep and broken in summer, which means that in spring a light covering of snow hides innumerable hidden crevasses. Many of the larger crevasses were already open, and occasioned much trouble in choosing a route.

Neal Carter, Hazen Nunn, Alpha & Serratus Mountains - April 1925

Hazen Nunn continues the story.

Leaving the ridge, we traversed below a series of cliffs and roped up on the margin of the glacier. A peculiar feature of Tantalus Glacier is a nunatak rising some 200 feet above the ice. This rocky pinnacle, which, owing to its shape, we called the Horn, is situated below the peak, and our course was directed towards it. At 2:30 we reached it and found the altitude to be 7,300 feet. As the peak was known to be at least 1,000 feet higher, we decided, in view of the exhausting trail breaking, to renew the attempt the next day.

Nunn, Townsend & Carter "Flashlight of the 1925 Party"

Day 4: Second Attempt on Tantalus

On day 4 they set out on their second attempt to reach the summit of Mt. Tantalus. Neal Carter described the day:

With greater hope of success, a fresh attempt was commenced the following morning and splendid time made over the already broken trail. In places, wind-drifted snow had filled it overnight, but the "Horn" at 7000 feet was reached over two hours earlier than before. From here the ascent lay up a tremendous steep slope of soft snow to a pass just below the peak; but many hours were spent battling with the crevasse stretched completely across between cliffs of the peak on one side and a rocky inaccessible ridge on the other. It looked as if progress was barred but, fortunately, a narrow ridge of snow at an angle of 45 degrees was left unmelted, and over this the party crossed with much misgiving. Once over the top of the pass a wonderful view was obtained of the country to the south between the head of Jervis Inlet and Howe Sound. The peak could be seen rising some 500 feet higher to the left, and since there seemed to be no immediate difficulty, our hopes of success were high.

Hazen Nunn & Chas Townsend Approach Tantalus Summit - April 1925

Half an hour later, however, it was discovered that a narrow ridge of overhanging snow lay just in front of us, separating the summit by some 200 feet linear distance. It was deemed imprudent to attempt to cross this, for if it gave way during the process, a 6000-foot drop to the Clowholm Lakes on one hand and a 1000-foot drop to the head of the Rumbling Glacier on the other would have been sure to have put our aneroid out of order. Hence one of the most galling events had to be endured; that of stopping short of the summit. Our elevation was 8800 feet and the summit about seventy-five feet higher.

Hazen Nunn wrote about the beautiful view from the summit ridge.

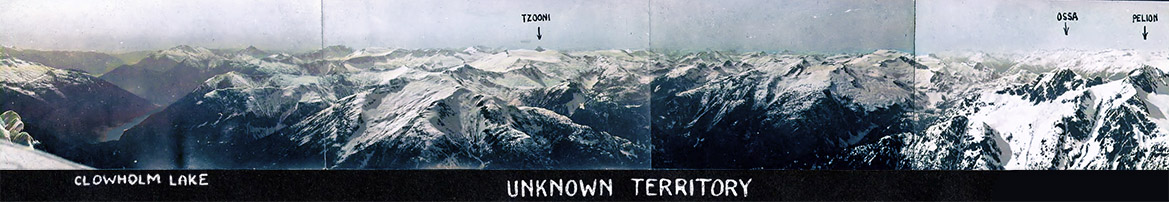

From the summit ridge a wonderful panorama was enjoyed in all directions. Almost directly below us lay Clowholm Lake and Narrows Arm. This locality was once proposed as the site of a summer camp, but we could see that the peaks are not as imposing as was thought at that time. To the north lay the vast dissected coast peneplain reaching far up into the Lillooet country. The whole length of the Squamish valley could be seen, and the river followed from its headwaters down its winding course to the sea. We had a very fine view looking down on the Garibaldi range, and various features in the 1924 summer camp district were recognized.

Tantalus Summit Ridge Panorama - April 1925

Charles Townsend & Hazen Nunn Tantalus Summit Ridge - April 1925

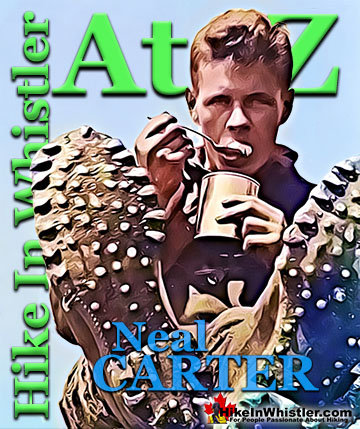

Neal Carter Mountaineer & Explorer

Charles Townsend's friend and climbing partner Neal Carter has an amazing history of exploration. These are some highlights of his remarkable days as one of BC's greatest mountaineers.

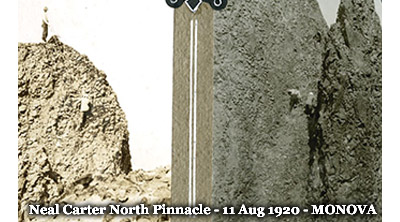

1920: Black Tusk North Pinnacle

1920: Black Tusk North Pinnacle

Neal Carter's impressive mountaineering feats began at an astounding pace. In 1920, Tom Fyles, Neal Carter and Bill Wheatley made the first known ascent of the north peak of Black Tusk. Slightly higher and just a few metres from main summit, known officially as the true summit. This terrifying feat involved climbing down the crumbling edge of Black Tusk into a gully and up the north pinnacle. Surrounding the pinnacle is a vertical drop of hundreds of metres and most of the surface rock is fractured and finding a solid handhold to climb is difficult. Likely a spur of the moment idea by Tom Fyles, who had the extraordinary ability to climb anything and was absolutely fearless. Continued here...

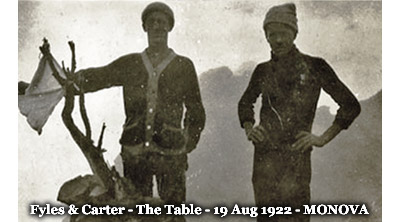

1922: The Table Second Ascent

1922: The Table Second Ascent

In 1922, Neal Carter, Tom Fyles and Bill Wheatley successfully climbed The Table, a mountain so difficult and dangerous that even today, few have climbed it. Theirs was only the second recorded ascent of The Table, with Tom Fyles making the first ascent in 1916. The Table is a crumbling, flat topped mountain that formed as a volcano pushing its way to the surface of a glacier. Located across Garibaldi Lake from Black Tusk, The Table is similarly crumbling and its steep sides make it incredibly hard to climb. In 1922, Fyles reached the top once again and Carter and Wheatley followed with help from Fyles’ rope from the summit. Continued here...

1923: Wedge & Whistler Expedition

1923: Wedge & Whistler Expedition

In the summer of 1923 Neal Carter and Charles Townsend went on an incredible two-week climbing expedition around what is now Whistler. They set off from Rainbow Lodge and climbed the previously unclimbed Wedge Mountain. From the summit of Wedge they spotted a mountain to the north in the midst of a maze of glaciers. They named it Mount James Turner and managed its first ascent as well. In the following days they hiked up Singing Pass and to the summit of Overlord Mountain. They made first ascents of two peaks, which they named Diavolo and Whirlwind. Carter left photos at Rainbow Lodge and now they reside in Whistler Museum. Continued here...

1924: Climbing in the Tantalus Range

1924: Climbing in the Tantalus Range

In the spring of 1924 Neal Carter set out on his second expedition into the Tantalus Range with Hazen Nunn, Ted Taylor, Art Cooper and Fred Smith. Mount Tantalus was their main goal, however, deep springtime snow, bad weather and difficult route finding barred their attempt. Despite not reaching the summit of Tantalus, the expedition reached the summits of several other prominent mountain peaks, such as Alpha, Pelops, Dione and Omega. Along the way they named several unnamed mountains in keeping with the Greek myth of Tantalus. Niobe, Pelops, Dione, Sisyphus and Pandareus are all names created by Neal Carter on this remarkable expedition in 1924. Carter's beautiful photo album of the expedition is now at the MONOVA Museum in Vancouver. Continued here...

1925: Fighting Way to Mt. Tantalus

Neal Carter's third expedition into the Tantalus Range was with Charles Townsend and Hazen Nunn. This time the trio of expert mountaineers set out to finally reach the summit of Tantalus. They battled through brutally steep, difficult and dangerous terrain over glaciers and terrifying ridges. With just a couple hundred metres from the summit the knife edge, snow covered ridge gave way to a deep chasm, too dangerous to cross. Despite the unsuccessful attempt, the expedition was later written about by Carter in a thrilling article in the Vancouver Sunday Province, along with some amazing photos taken along the way. Carter also created a wonderful photo album of the expedition which now resides in the MONOVA Museum in Vancouver. Continued here...

1932: Meager Expedition

1932: Meager Expedition

August 8th-20th, 1932 Neal Carter, Tom Fyles, Mills Winram and Alec Dalgleish went on a spectacular mountaineering expedition up the headwaters of Lillooet River to Mount Meager. On day 5 Carter recalled, "the toe of a likely looking ridge at an elevation of 1750 feet opposite some hot springs on the bank of the creek was reached." The hot springs they saw are now well known as Meager Hot Springs. In the following days they climbed all six of the volcanic peaks of the Mount Meager massif and named the five unnamed ones. Mount Job, Capricorn Mountain, Devastator Peak, Plinth Peak and Pylon Peak were named. Beyond Meager, unknown peaks stretched to the ocean and another expedition was planned. Continued here...

1933: Toba Expedition

1933: Toba Expedition

The unknown mountains they saw from Mount Meager in 1932 were located at the headwaters of Toba River, which drained into Toba Inlet far up the coast of BC. In 1933, Neal Carter, Tom Fyles, Mills Winram and Alec Dalgleish teamed up again to explore this vast unknown. The remote Toba Inlet was reached by boat and the expedition involved boating upriver for several miles, then hiking great distances through near impenetrable forest. Despite weathering brutal terrain, considerable bushwhacking, and dangerous river crossings, they managed to make the first ascent of a towering and forbidding mountain they named Mount Julian. Continued here...

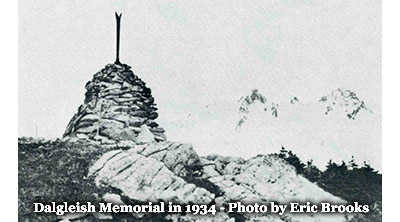

1934: Waddington Tragedy

1934: Waddington Tragedy

After the Toba Expedition, Alec Dalgleish set his sights on what was the greatest mountaineering prize of the era, the still unclimbed Mount Waddington. The highest peak in the Coast Mountains and requiring a journey of several days to get to. Neal Carter and Eric Brooks joined this brutally challenging expedition to this remote mountain in 1934. The remoteness and difficulty of Waddington was vastly more than the Toba Expedition. The assault on Mount Waddington would end in tragedy however, when Alec Dalgleish fell to his death while on a roped descent along a smooth, outwardly sloping ledge. His belaying rope did not save him as it was cut by the sharp edge of a frost-shattered rock. His body could not be recovered. Continued here...

More Whistler & Garibaldi Park Hiking A to Z!

The Best Whistler & Garibaldi Park Hiking Trails!

Whistler & Garibaldi Park Best Hiking by Month!

Explore BC Hiking Destinations!

Whistler Hiking Trails

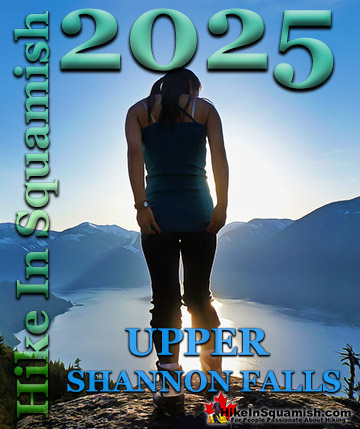

Squamish Hiking Trails

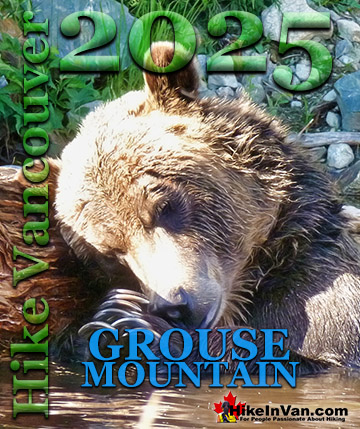

Vancouver Hiking Trails

Clayoquot Hiking Trails

Victoria Hiking Trails