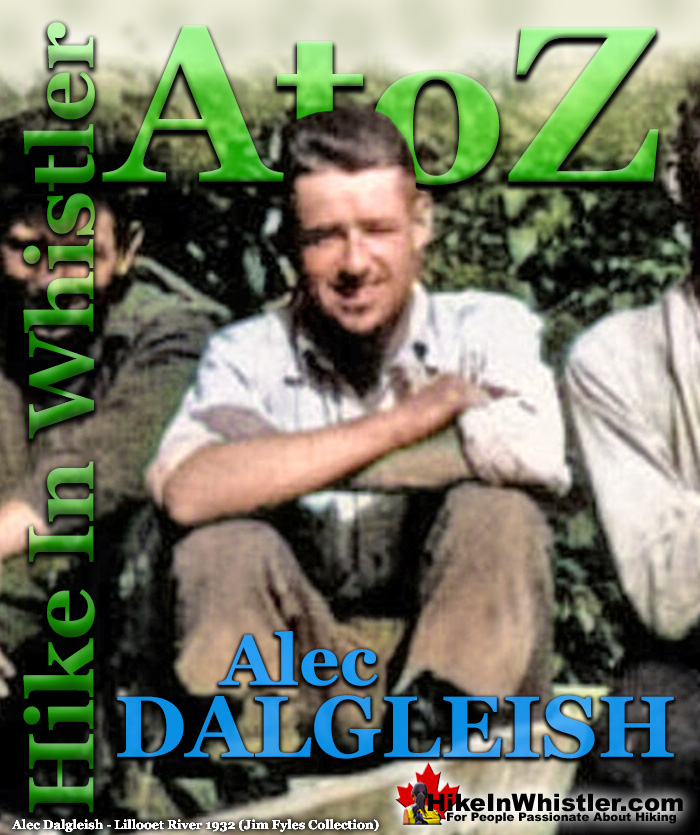

![]() Alec Dalgleish (1 August 1907 - 26 June 1934) was a highly respected mountaineer and climber out of Vancouver in the 1920's and 1930's. His enthusiasm and dedication to climbing was boundless. He used The Camel, a vertical cliff on Vancouver's Crown Mountain to train. Though commonly done today, in Dalgleish's day, training for rock climbing was very unusual and underscored his drive to excel at the nascent sport of climbing. In the late 1920's he became friends with Tom Fyles, a veteran Vancouver mountaineer and arguably the greatest climber of the era.

Alec Dalgleish (1 August 1907 - 26 June 1934) was a highly respected mountaineer and climber out of Vancouver in the 1920's and 1930's. His enthusiasm and dedication to climbing was boundless. He used The Camel, a vertical cliff on Vancouver's Crown Mountain to train. Though commonly done today, in Dalgleish's day, training for rock climbing was very unusual and underscored his drive to excel at the nascent sport of climbing. In the late 1920's he became friends with Tom Fyles, a veteran Vancouver mountaineer and arguably the greatest climber of the era.

Whistler & Garibaldi Hiking

![]() Alexander Falls

Alexander Falls ![]() Ancient Cedars

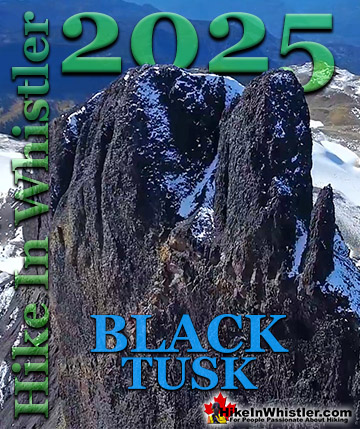

Ancient Cedars ![]() Black Tusk

Black Tusk ![]() Blackcomb Mountain

Blackcomb Mountain ![]() Brandywine Falls

Brandywine Falls ![]() Brandywine Meadows

Brandywine Meadows ![]() Brew Lake

Brew Lake ![]() Callaghan Lake

Callaghan Lake ![]() Cheakamus Lake

Cheakamus Lake ![]() Cheakamus River

Cheakamus River ![]() Cirque Lake

Cirque Lake ![]() Flank Trail

Flank Trail ![]() Garibaldi Lake

Garibaldi Lake ![]() Garibaldi Park

Garibaldi Park ![]() Helm Creek

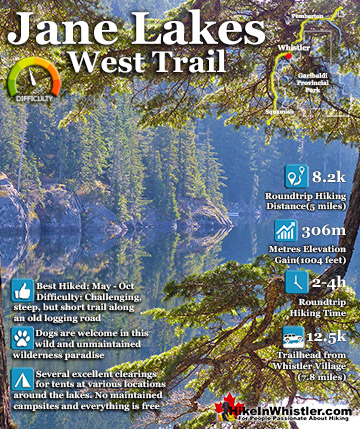

Helm Creek ![]() Jane Lakes

Jane Lakes ![]() Joffre Lakes

Joffre Lakes ![]() Keyhole Hot Springs

Keyhole Hot Springs ![]() Logger’s Lake

Logger’s Lake ![]() Madeley Lake

Madeley Lake ![]() Meager Hot Springs

Meager Hot Springs ![]() Nairn Falls

Nairn Falls ![]() Newt Lake

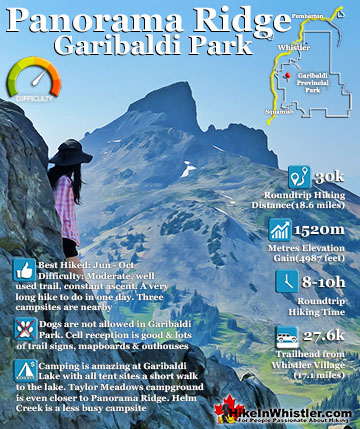

Newt Lake ![]() Panorama Ridge

Panorama Ridge ![]() Parkhurst Ghost Town

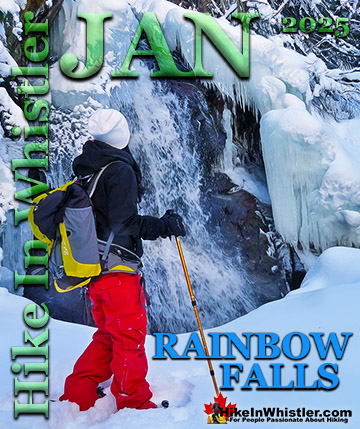

Parkhurst Ghost Town ![]() Rainbow Falls

Rainbow Falls ![]() Rainbow Lake

Rainbow Lake ![]() Ring Lake

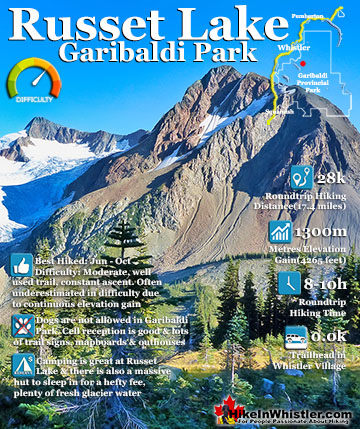

Ring Lake ![]() Russet Lake

Russet Lake ![]() Sea to Sky Trail

Sea to Sky Trail ![]() Skookumchuck Hot Springs

Skookumchuck Hot Springs ![]() Sloquet Hot Springs

Sloquet Hot Springs ![]() Sproatt East

Sproatt East ![]() Sproatt West

Sproatt West ![]() Taylor Meadows

Taylor Meadows ![]() Train Wreck

Train Wreck ![]() Wedgemount Lake

Wedgemount Lake ![]() Whistler Mountain

Whistler Mountain

![]() January

January ![]() February

February ![]() March

March ![]() April

April ![]() May

May ![]() June

June ![]() July

July ![]() August

August ![]() September

September ![]() October

October ![]() November

November ![]() December

December

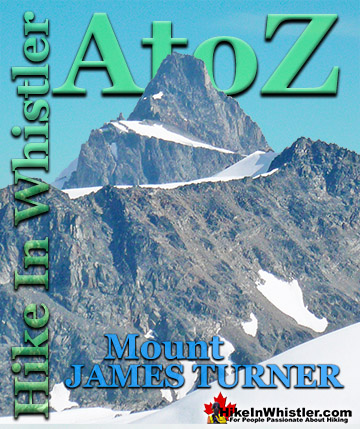

Alec Dalgleish and Tom Fyles became close friends and embarked on several pioneering expeditions into the still unknown regions of the Coast Mountains. In 1930 they, along with Stan Henderson, explored the source of the Teaquahan River at the head of Bute Inlet. They were the first climbing party to venture onto the enormous Homathko Snowfield and the first to summit Bute Mountain. In 1932 Dalgleish and Tom Fyles teamed up once again, this time with Neal Carter and Mills Winram. They explored up the headwaters of Lillooet River and made a series of first ascents on and around Mount Meager. From their towering vantage point they saw countless unnamed peaks stretching to the ocean. The following year, in 1933 they all set off on another remarkable journey into the unknown headwaters of Toba River. Despite weathering brutal terrain, considerable bushwhacking, and dangerous river crossings, they managed to make the first ascent of a towering and forbidding mountain they named Mount Julian. The next mountain Dalgleish set his sights on was the greatest prize of the era, the still unclimbed Mount Waddington. In his book, Pushing the Limits: The Story of Canadian Mountaineering, Chic Scott writes that, "He was one of the few local climbers who might conceivably have had a chance at climbing Mount Waddington."

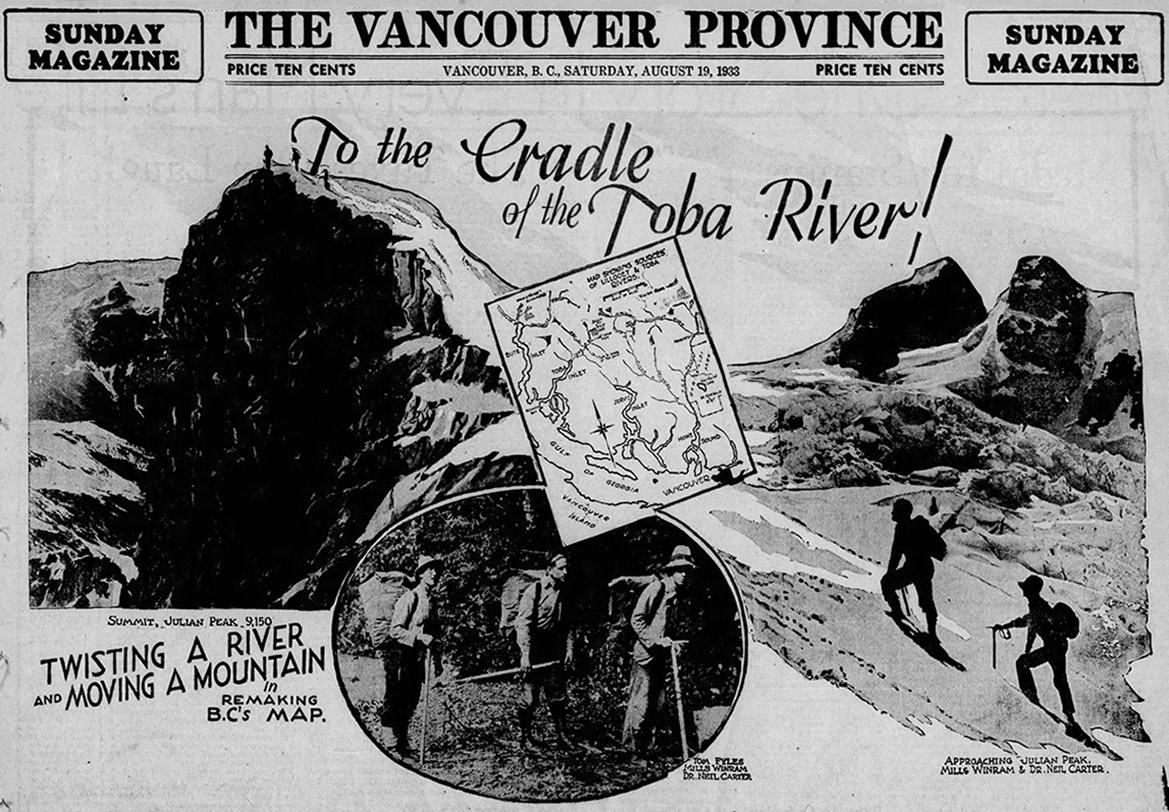

1933: To the Cradle of Toba River!

Alec Dalgleish, Tom Fyles, Neal Carter & Mills Winram

From their towering vantage point on Mount Meager in 1932, Alec Dalgleish, Tom Fyles, Neal Carter and Mills Winram saw for the first time, the vast range of unknown snowy peaks stretching west to the ocean. Carter recalled that moment in his article ‘Exploration in the Lillooet River Watershed’ he wrote in the Canadian Alpine Journal in 1932, "An entirely unknown, heavily glaciated range over 9000 feet high lay some dozen miles to the west, behind which the tips of several peaks exceeding 10,000 feet in elevation could be distinguished. These lay in the direction of the headwaters of the Toba River and it was evident that they would have to be approached from that direction." Alec Dalgleish recalled, "how we sat on the summit of Meager Mountain, a hitherto unclimbed peak of the B.C. Coast Range and vainly endeavored to identify the snowy ranges which rose to the north and west. The desire to view these peaks more intimately grew within us during the following winter and we finally decided to explore the source of the Toba River which we thought might lead us into them.” In 1933, Dalgleish, Carter, Fyles, and Winram would embark on another mountaineering expedition into the unknown mountains and glaciers at the source of Toba River.

To the Cradle of the Toba River! by Alec Dalgleish

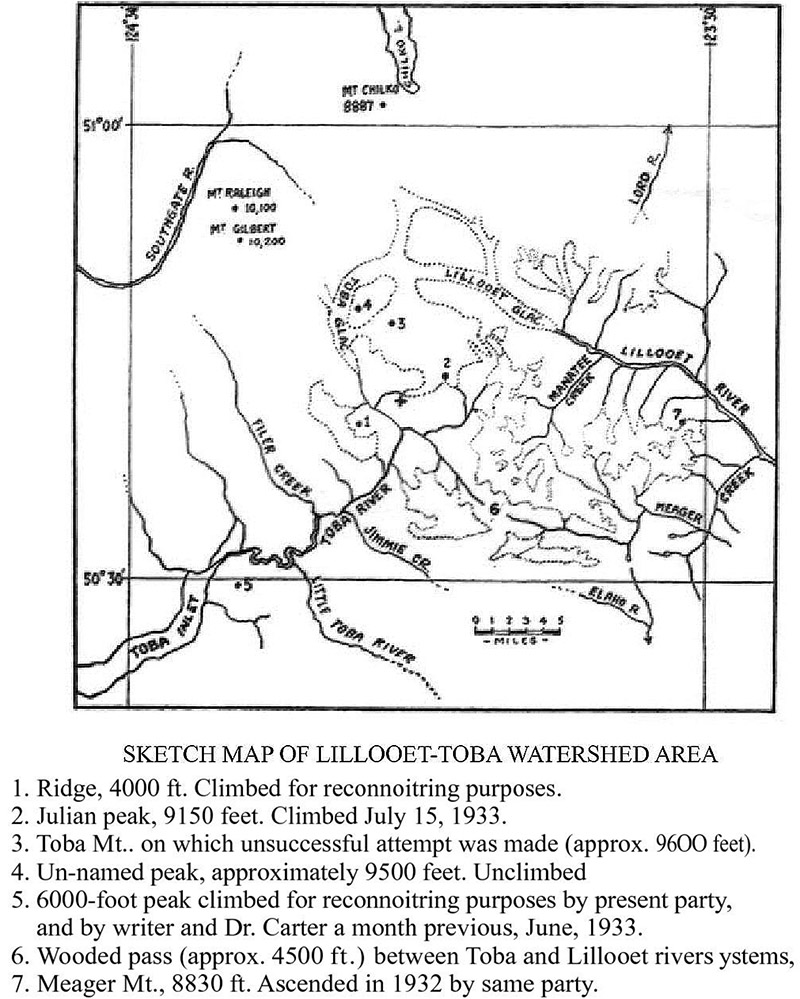

Dalgleish wrote two wonderfully detailed articles about their ambitious, second expedition in the summer of 1933. One appeared in the 1933 edition of the Canadian Alpine Journal and the other in the Vancouver Province on August 19th, 1933. Both articles wonderfully detailed their journey almost day by day, and you quickly get a sense of the brutal terrain they faced through they faced bushwhacking for miles through harsh and unknown terrain. The Province article “To the Cradle of the Toba River!” was illustrated with a drawing, photo and map. The Canadian Alpine Journal article titled, “The Source of the Toba River” includes eight photos taken by Dalgleish, as well as detailed map drawn of the area they covered. Mills Winram was interviewed in 1979 about his past hiking adventures and talked about the Toba hike. The interview was printed in the excellent book, In the Western Mountains: Early Mountaineering in British Columbia, published in 1980. The following is a day by day account of their expedition as recalled by Dalgleish and Winram.

Day 1: Vancouver to Toba Inlet

On Saturday, July 8th, 1933 Alec Dalgleish, Tom Fyles, Neal Carter and Mills Winram boarded the steamship Chelohsin in Vancouver to begin their 250 kilometre boat journey to Toba Inlet.

Carter, Winram & Fyles on the Chelohsin - 8 July 1933

Day 2: Head of Toba Inlet

The Chelohsin arrived at Redonda Island in Toba Inlet at 4am on Sunday morning, July 9th, 1933. Dalgleish recalls:

Here we were met by Bill and Joe Barnes, sons of Walter Barnes, trapper and farmer of Toba Inlet, and his Indian wife. We stowed our supplies in their dilapidated though dependable gas-boat and were soon chugging our way through the winding channels whose waters changed slowly from deepest blue to glacial green as we neared the head of the inlet. At half past one we reached the head. Progress up the river would have to be delayed until high tide at 6:30 the following morning. The weather was glorious and a snowy peak rising some six thousand feet above Bill Barnes’ little shack invited us to climb it and see what was up the river.

We made elevation rapidly on an open timbered ridge, thickly populated by large and hungry mosquitoes. At 6 o'clock we reached the summit but the sky had clouded over and all we could see beyond the head of the river was a great, white, glacier-clad slope, the peaks above hidden in the clouds—thirty miles away it must be as the crow flies—but we hoped for the best and put our trust in the gas boat.

We left the peak by 7 and descended the last two thousand feet in darkness and a driving rain. In a log chute a few hundred feet above the salt chuck I slipped and fell some ten feet between two huge logs. My heartless companions roused me from blissful unconsciousness and the descent was completed without further mishap. We descended in darkness and rain to spend the last few hours of the night on the rough floor of Joe Barnes’ shack among his numerous children.

Day 3: Boat Journey Up Toba River

On Monday, July 10th, 1933 they were finally able to start their long boat journey up Toba River battling the strong current and with the weather turning to rain. Dalgleish continues the story:

With the high tide on Monday morning, we started up the river and at 2:30 in the afternoon reached the first forks, sixteen miles from the inlet. Here we transferred from the gas boat to a dugout canoe with outboard motor and continued on our way. With the weight of six men and our far from inconsiderable packs the canoe made slow headway against the rushing waters. Concealed snags were a constant menace to the fragile bottom of our craft but we escaped damage, thanks to the keen eyes of Bill and Joe. The going in the torrential river became slower, sometimes we barely seemed to crawl. Again, a patch of slow water allowed us to shoot ahead at a more encouraging speed. Soon we had to reinforce the kicker with the oars and about 7 p.m. reached a deserted hand-logger's cabin and decided to spend the night.

Day 4: Canoeing Up Toba River

On Tuesday, July 11th they continued up Toba River by canoe, fighting against its ever increasing current, making painfully slow progress. Dalgleish continues:

After spending the night in a deserted logger’s cabin, we continued in the canoe on Tuesday. The river grew swifter and swifter and finally we took to the shore while Bill and Joe cajoled the canoe along with pole and kicker. It was slow going, but so long as progress was being made the packs were more comfortable in the canoe than on our backs. At noon we came to a rapid and decided that the time to backpack had come at last. We had travelled twenty-five miles of the river by boat. Unfortunately, so snake-like are the windings of the Toba that our airline distance from the head of the inlet was only about fifteen miles.

Fyles, Winram & Carter Toba River - 11 July 1933

After bidding farewell to Bill and Joe who were to meet us at this spot eleven days later, we divided our supplies into four packs, finding to our surprise that these weighed but fifty-five pounds each. Surplus equipment was left in a trapper’s cabin nearby, the last habitation on the Toba River. We followed a sketchy trapper’s trail along the river bank. Sometimes the trail was good but it had a disconcerting trick of petering out in the midst of almost impenetrable tangles of devil’s club, vine maple and other exasperating Coast Range vegetation. For the rest of the day we plodded along the riverbank, sometimes on a sketchy but recognizable trail and again wrapped in clinging devil's club and salmonberry bush, fighting for minutes at a time to gain fifteen or twenty feet. At 9 p.m. we camped on a ten-foot strip of sand bar by the side of the river.

Day 5: Bushwhacking

Wednesday, July 12th, 1933, day 5 of their expedition was a day of little progress as the bushwhacking continued. Dalgleish has little to say about this day:

On Wednesday we struggled along all day and in the afternoon the river swung sharply to the north, shamelessly contradicting the north-easterly course shown on the map. We followed its new course for half a mile on a beautifully open gravel bar before camping.

Day 6: First Glimpse of Source of Toba River

On Thursday, July 13th, the sixth day of their expedition they finally were able to see the peaks and glaciers at the source of Toba River. They could finally plan their exciting days of alpine hikes. They also became aware of how they had just three days of climbing before having to start the long descent back down the river. Dalgleish wrote in his Vancouver Province article:

Next day two hours travelling brought us to two equal branches of the river, one continuing to the north, the other coming in from the east. Without reluctance we left our packs upon the bar and made a hurried ascent to a height of 4500 feet on the ridge to the west. At last we could see the actual sources of the river. The northern branch flowed from a sinuous green glacier some two or three miles above the forks, cascaded over a band of cliffs, tore its way through an amazingly narrow cleft in a ridge of rock and then tamed down a little for the final mile before joining the east branch. The north branch glacier appeared to descend to a very low level, between one and two thousand feet above sea level; the east branch came also from a large glacier about the same distance from the confluence but somewhat higher, perhaps twenty-five hundred feet above the sea.

What drew our attention most however, was a massive peak which reared its impressive bulk at the head of the east branch glacier. Great ice-falls half masked in snow draped its shoulders from which rose a double peak, one chisel-shaped, the other a sharp rock tusk. A difficult thing to explain to the non-mountaineer but it was just one of those peaks! It must be climbed, even if we climbed nothing else. In solemn conclave that evening we apportioned the rest of our time. We would pack five days grub up the east branch. A day in and a day out would allow three days to climb. Then a day to explore the source of the north branch and two days to get back down river to meet the canoe.

Day 7: The Nose of the Glacier

On Friday, July 14th, 1933 they packed five days worth of supplies and hiked up the east fork. In his Vancouver Province article Dalgleish wrote:

Friday was clear and hot as we slowly mounted along the side-hill, packs now reduced to about forty pounds. The underbrush was reasonably penetrable but it was 5pm when we threw down our packs on a flat space of gravel not fifty feet from the great mud covered nose of the glacier. Our elevation was only twenty-seven hundred feet above the sea, yet all about us stretched a waste of rock and ice. For wood we must resurrect bits of smashed and gritty tree trunks brought down from the higher benches by snowslides. Two or more miles farther on, our chosen peak thrust its sharp rock summit from the clinging ice-falls of the glacier. We climbed into our bags early that night, dedicating the next day to its ascent.

Day 8: Summit of Julian Peak

On Saturday, July 15th they reached the summit of an unknown peak which they named Julian Peak. Julian Peak turned out to be the only mountain they climbed. Mainly this was due to the short window of time that had to climb, but also due to the difficult and time consuming glacier travel required to reach the nearby summits. Weather would also cause delays by reducing visibility so much as to make navigating the maze of glacier crevasses near impossible. Yet another difficulty they faced was caused by the brutal ordeal they faced hiking. Mills Winram described the days leading up to the 15th their battered condition they were in when they climbed Julian Peak:

It turned out we only climbed one mountain. which was later named Mount Dalgleish, after one of the members of our party who was killed on Mount Waddington the following year. But as to the bushwhacking part, that valley had an awful lot of devil's club. And we hadn't taken our gloves with us, so in spreading the branches apart, we inevitably got lots of thorns in our fingers, and they became painfully infected. And some days, we couldn't go further than three or four miles and then we'd struggle out to the shore of the river and camp on the gravel bars. And then next morning, we'd waken about 4 or 4:30, have a quick breakfast, put on our pack and struggle on through the bush again. The weather had been cool and rainy, so when we got up near the headwaters, the river was down, and we were able to cross it quite easily. It would be maybe fifty feet wide at that point, and it didn't go much over our boot tops. And then we went up to where the river came out of the snout of what is now the Dalgleish Glacier, and we camped on the gravel there. The next day we made our climb right up to the peak, which is about 9,700 feet, and came back to our camp.

In his newspaper article ‘To the Cradle of the Toba River’ Dalgleish wrote about July 15th, 1933 in great detail:

Before daylight we were up and as the first glints of sunlight appeared on the highest peaks we crossed the tongue of the glacier and started up a steep, rocky slope. Above it we knew lay the upper snowfields which mounted in great icy curves to the summit. The rocks were soon passed but we were still far below timberline and more than two hours were consumed in fighting through the inevitable tangle of slide alder which clings to any avalanche-swept slope below the five thousand foot mark.

At last the upper glacier was reached and we roped up before threading our way through the maze of crevasses which criss-crossed its snowy surface. Some were good honest gaping holes but others were treacherously masked beneath a thin layer of snow. The snow grew softer under the growing heat of the sun and we plodded more and more slowly up the glaring slopes, eyes sheltered by dark glasses, and a protective coating of grease paint on our faces, At two in the afternoon we stepped on the summit, our aneroids giving the altitude at 9150 feet. It was a perfect day, and all the peaks from Mt. Garibaldi in the south to Mt. Waddington in the north were spread out around us. These are the moments which fully reward the mountain climber for all his hours of labor.

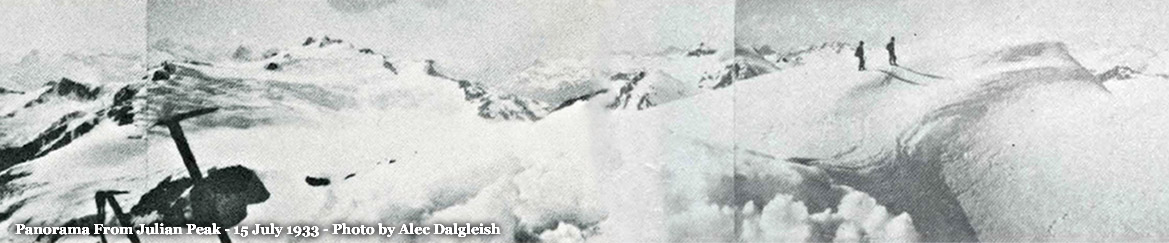

Julian Peak - 15 July 1933

We sat long on the peak, taking photographs and angles and scanning the horizon with binoculars to recognize old friends and make vague speculations on future ascents of various previously unseen peaks which bulked above the lesser ranges. Two huge peaks rose to the north somewhere near the Bishop River. Our shoulders ached at the thought of the back-packing necessary to reach them.

View West From Julian Peak - 15 July 1933

We felt it our privilege, as the first climbers, to apply a name to the peak we were on, and it was decided to call it Julian Peak in honor of the old Toba Indian chief. He is eighty-six years of age and still lives at the head of Toba Inlet where he was born. As a boy he had crossed from the head of the Toba River into the Lillooet. Toba Mountain would seem appropriate for the higher peak (approximately 9600 feet) to the northwest, as it is the highest point on the Toba River drainage system. We left at last and descended the mushy snowfields, avoiding the morning's tangled bush by a detour on steep rock, and reached camp by fading evening light.

Alec Dalgleish Below Julian Peak - 15 July 1933

Day 9: Rest and Recover

Sunday, July 16th, 1933 was devoted to resting and recovering. Dalgleish wrote briefly of the day:

Sunday was a day of rest, more, I am afraid, for the good of our bodies than our souls. Mills had a very sunburnt face due to his child-like faith in the anti-actinic properties of castor oil, and I was quite lame with an infected sliver in the calf of my right leg. Tom’s hands were very sore from the effects of devil’s club needles. The familiar spirits of the Toba River apparently resented our intrusion.

Day 10: Toba Mountain

On Monday July 17th, 1933 while Dalgleish rested at the camp, Fyles, Carter and Winram set out to climb Toba Mountain. Dalgleish described the day:

On Monday, Tom, Neal and Mills made an attempt upon Toba Mountain. Attempting to follow a route which appeared feasible as seen from Mt. Julian, they found themselves in dense fog amidst a maze of crevasses. Crossing toward the southeast face to avoid these, they managed to ascend the east ridge to a height of 8400 feet where a combination of fog and general bewilderment as to the nature of intervening glacier-covered ridges forced them to turn back after spending over two hours huddled in a scooped-out hole waiting for the clouds to lift. On descending to the great snowfield which lay between Toba and Julian they got below the fog and decided to explore its northern extremity. Almost an hour and a half was required to reach this point but they were rewarded with a view of the upper reaches of the great Lillooet River Glacier. These appeared to originate chiefly in the snowfield on which the party stood, though other tributaries came in from the north. The ice also sloped to the west and almost certainly curved around the west side of Toba Mountain to feed the north branch of the Toba River.

About 8pm, in heavy rain, they squished into camp and made short work of a huge pot of macaroni and dried vegetables over which I had brooded with dripping jaws all afternoon. A council of war was held that night over my right leg. It was swollen to regal proportions and colored in delicate shades of violet and magenta. Four days remained until we met Bill and Joe down the river and it had taken us three to reach this point. Handicapped by a cripple we must allow ourselves plenty of time to get out. Sadly we decided that we would start the retreat on the morrow.

Day 11: Begin Hiking Out

On Tuesday, July 18th, 1933 they began their return journey. Dalgleish wrote:

Despite two days rest my leg was still worse on Tuesday morning and as we were to meet Bill and Joe on Friday we decided that we must start out at once. I forced a climbing boot upon my protesting limb and by evening we were back at the junction of the north and east branches.

Day 12: Crossing Toba River

Mills Winram recalled the difficult river crossing they faced on their return journey on Wednesday, July 19th, 1933:

By this time, Alec Dalgleish had a bad infection in his heel, and he could hardly walk without the aid of a cane. So we hobbled down the glacier to the place where we had crossed the river. Only it had been hot weather in the interval, and now the river was about six feet deep, and roaring down full of mud and boulders. We knew we couldn't cross it in that state. So we cut down a tree, hoping to bridge it that way, and the first tree we cut down was swept away almost at once. And then we tackled a big cedar, a partially dead tree about three and a half feet at the butt. And after an awful lot of work with one little axe, it did come down and it bridged the river. And water rushed across the middle of it about three or four inches deep, and it shook with the force of the current. But we had to get across. I grabbed my pack and I rushed right across, and I wouldn’t have gone back over that thing for anything. Neal Carter came across after me, and then Tom Fyles came across carrying his own pack, and helping Alec Dalgleish who couldn't balance himself alone. And somebody had to go back and get Alec's pack, so Tom made a second trip across that awful log, which I'm sure went out in the next hour.

Tom Fyles Crossing With Dalgleish's Pack - 19 July 1933

Neal Carter crouching in the middle of Toba River waiting for Tom Fyles to come across his second time after getting Alec Dalgleish's pack.

Day 13: Trapper's Cabin

Thursday afternoon on July 20th they arrived at the trapper’s cabin where they arranged to meet the boat the following day.

Day 14: Canoeing Down Toba River

Dalgleish wrote briefly about Friday, July 21st, 1933: "Friday, while Tom and Neal engaged in a titanic struggle with the bluffs and bushes of a nearby hillside, Mills and I loafed on a gravel-bar and joyfully hailed the canoe as it crept around the bend that afternoon."

Day 15: Toba River to Toba Inlet

On Saturday, July 22nd, fifteen days from when they started, they emerged from the wilderness and back to the farmhouse on Redonda Island in Toba Inlet. Dalgleish wrote: “The swift return trip down the river made without incident, though we will long remember the dinner set before us by Mrs. Mattson, mother of one of the Toba River farmers.”

Day 16: Depart Toba Inlet by Boat

On Sunday afternoon on July 23rd they were on the boat back to Vancouver and Dalgleish recalled, “Monday morning, July the twenty-fourth we slid through the First Narrows, back once more, with mixed feelings of joy and regret, to the land of street cars, sidewalks and clean shaves.”

Mills Winram recalled their journey back to Vancouver and reflected on what the Toba expedition meant to him when interviewed in 1979:

At mealtime, the waiter wouldn't let me sit in the little dining room on the boat because I had this great running sore - a spectacular hit from a devil's club thorn. Poor Alec Dalgleish was worse than me because he was limping from his bad heel. And the others looked puffy, and their skin was all burnt out from glacier burn, and infected with thorns. It took me at least a month and a half after that just to get back my full energy. I was sleeping quite a lot to get over it. I suppose it's something like a military campaign. After you've really struggled very, very hard physically, you have to relax for a while.

But we saw a place that no one else had been. We knew we could do what no one else had done; there were a few other people who could do it, but we had managed to do it. And this is a reward you can claim without paying taxes on it. It's just curiosity. If no one else has been there, it’s a sort of fatal attraction. It may not sound like much, but when this fellow Mallory was asked in 1924 why he bothered to try to climb Mt. Everest, he couldn't think of any other reason, except to say no one else had been there, and therefore he'd like to see what it was like. And that's the way we felt.

Dalgleish's Canadian Alpine Journal Article Map

1934: Waddington Tragedy

In 1934 Alec Dalgleish, Neal Carter, Eric Brooks and Alan Lambert set out to conquer Mount Waddington, a brutally difficult, remote peak widely regarded as the best known, unclimbed mountain in North America. Their attempt on British Columbia’s third highest mountain would end in tragedy when Alec Dalgleish fell to his death while on a roped descent. An article in The Vancouver Daily Province described the accident:

Mr. Dalgleish started to descent to Brooks, who was next to him on the rope, which was anchored between them over a projection of rock. Suddenly Brooks saw Dalgleish slip to the side of the ridge over a bulge of rock and out of sight. An impact was felt and at the same time the full strain came on the rope, which parted between Dalgleish and Brooks. Dalgleish fell about 100 feet to the snow below, down which he was carried for about 500 or 600 feet.

It is hard to appreciate how incredibly difficult Waddington is to navigate, though the time it took for these expert climbers to reach Dalgleish’s body is astonishing. Three and a half hours was spent descending the maze of cliffs to get to him where they could tell right away that he had died immediately.

The Spectacular and Brutal Waddington Range

The difficulty of Waddington is hard to appreciate. This is a wonderful video by Brian Dickinson which shows the spectacular and brutal terrain of the Waddington Range.

Mystery Mountain

In 1925 Don and Phyllis Munday stood on the summit of Mount Arrowsmith on Vancouver Island. Far to the north, they spotted an impressive and unknown mountain which they thought might be the highest mountain in BC. They named the mountain Mystery Mountain, though it later was renamed Mount Waddington. The Munday’s spent much of the next decade trying to make the first ascent on this brutally difficult and remote mountain. After several unsuccessful expeditions, they managed some success in 1928 when they reached the lower summit. They resolved that the main summit was too dangerous to attempt. Six years would pass before Waddington would be attempted again. Neal Carter recalled:

In the summer of 1933, while climbing in the peaks surrounding the headwaters of the Toba River, Alec Dalgleish had discussed the desirability of making an attempt on Mt. Waddington the following summer. During the intervening winter, plans were formulated by himself and Alan Lambert of the B.C. Mountaineering Club, Eric Brooks and the writer, who with Dalgleish were members of the Alpine Club of Canada, were invited to participate in the attempt.

They first had to travel the considerable distance by boat from Vancouver to Knight Inlet. They had 18 days for their expedition and the first six days were spent transporting their gear to their basecamp at Icefall Point. Several trips back and forth had to be made through the very difficult terrain to reach the foot of Franklin Glacier, where they then had to then make several more trips to Icefall Point. Carter’s detailed account of these days is interesting.

June 18th—One load from beach (6 p.m.) to camp two miles up-river (8 p.m.). June 19th—From above camp (7 a.m.) to foot of glacier (1 p.m.) and return to beach (8.45 p.m.). June 20th—Second load from beach (9.30 a.m.) to foot of glacier (7.15 p.m.). June 21st—From foot of glacier (10 a.m., 500 ft.) to cache on glacier opposite Confederation glacier (4 p.m., 3750 ft.) and return to foot (7 p.m.). June 22nd—Second load from foot of glacier (9.30 a.m.) to camp on Franklin glacier one half-mile above junction with Confederation glacier (5 p.m., 3950 ft.), picking up cache en route. June 23rd—From camp on glacier (4.30 a.m.) to Ice-fall point (7.20 a.m., 5000 ft.) on ski and trip back for second load, returning to Icefall point at 3 p.m.

A base camp at Icefall point was thus easily established and June 24th and 25th were spent around camp in making short excursions to the ridge above camp and to the pass at the head of the Repose Glacier. The face of Mt. Waddington was carefully studied and discussed on these reconnoitring trips and since these two fine days had removed practically all the fresh snow which had fallen on the mountain during the preceding few days, it was decided to make the first attempt on the peak on the 26th.

They left their camp at Icefall Point at 10pm on the 25th and spent several hours trying to find a feasible route to the summit. One promising route led them up a steep buttress, though eventually proved impassible. Carter continues the story in detail:

Dalgleish then commenced to descend, over the same route just taken by Lambert, while Brooks and the writer took in the slack rope over the belay. He had descended to within about 30 feet of the others when a slight scratching of nailed boots on the rocks above caused Lambert to look up just in time to see him disappear over the angle between the steep face of the buttress and its almost perpendicular side cliff that formed one wall of the snow gully that had been ascended earlier in the day. No exclamation or sound was heard as he fell. Brooks made a commendable effort to pull in the rope over the belay but did not succeed in gathering in more than a few feet when a terrific jerk which almost upset him occurred. He retained his grip on the rope, however, but the sliding of the taut rope down the sharp edge of a frost-shattered rock forming the angle of the buttress severed it within a few feet of his grasp. The rope, although it was the older of the two, did not suddenly snap under the strain, and the parting took place some distance from both the belay and the knot joining the two ropes.

Dalgleish could not be seen from the time he disappeared over the edge until he landed in the snow of the upper part of the main snow gully that had been ascended. This gully extended upward, roughly parallel to the route up the buttress, and consequently was never far below the edge of the buttress; the snow by this time had been softened by the sun. He immediately began to roll and bounce down the steep snow until hidden from view behind a bend at the foot of the buttress.

Profuse blood stains in the snow and the obvious fact that no effort was being made to check his descent down the gully indicated the seriousness of the situation. No sound came from below after waiting for some minutes so a descent as rapid as consistent with safety was begun. Only the shorter rope was now available for the three men and over three hours elapsed before the foot of the gully could be reached at 3.25 p.m.

A brief examination showed without doubt that death must have been instantaneous, caused by forcibly striking rocks before the relatively harmless descent of the snow gully occurred. No evidence of any movement having been made after coming to rest could be detected.

The next few hours were spent figuring out a way to transport his body to their basecamp. Their location was near the top of a thousand foot icefall on Buckler Glacier high above their basecamp. To reach their camp, under normal conditions, was an 8 hour descent over the glacier. Hours passed as they planned their descent and they soon concluded that the journey was not possible. They made a temporary burial in the neve snow and collected some of his personal effects. The return journey was difficult and dangerous as the weather turned foggy and they finally arrived at their camp at 2:30am on the 27th. The following day they set out on the long and difficult hike down to Knight Inlet. After 16 hours they arrived at the inlet on the 29th and from the Glendale Cannery they contacted the Provincial Police by radio. The following day they departed by boat to Vancouver. Carter wrote about the events of the following week:

The slopes of Mt. Waddington were chosen as the last resting place of Alec Dalgleish. Two of the original party, Lambert and Brooks, accompanied by Frank Smith and Stan Henderson of the A.C.C. and two of Dalgleish’s associates in former telephone constructional work left Vancouver a week later for the purpose of effecting a more permanent burial and erecting a suitable memorial at Icefall point. The writer was unable to accompany them owing to a severe injury sustained on the boat while returning from Knight inlet. This second party had no intention of climbing the peak and succeeded in carrying out all that was necessary; a large cairn incorporating Dalgleish’s skis and a suitably protected scroll now stands on a prominent elevation above Icefall point, facing the scene of the last endeavour of a true mountaineer.

A beautiful tribute to Alec Dalgleish appeared in The Canadian Alpine Journal soon after his death, which describes his memorial cairn.

On the sky-line of Icefall point above the Franklin Glacier stands and imposing cairn of granite rocks erected to the memory of Alec Dalgleish, whose form lies eight miles to the northeast, nestling as it were in the arm of the mighty Waddington, below the southern cliffs from which his gallant spirit passed on, while he was attempting, with his chosen companions, the conquest of that great peak on June 26, 1934. Others will take up the task he laid down and carry it to completion, but in the hearts of those who knew him he has left a record of a full and well-rounded life that in the years to come will prove a source of inspiration to those who shall follow after.

More Whistler & Garibaldi Park Hiking A to Z!

The Best Whistler & Garibaldi Park Hiking Trails!

Whistler & Garibaldi Park Best Hiking by Month!

Explore BC Hiking Destinations!

Whistler Hiking Trails

Squamish Hiking Trails

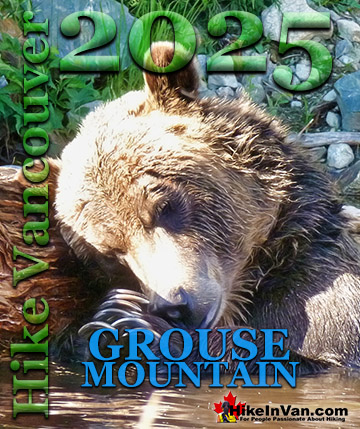

Vancouver Hiking Trails

Clayoquot Hiking Trails

Victoria Hiking Trails